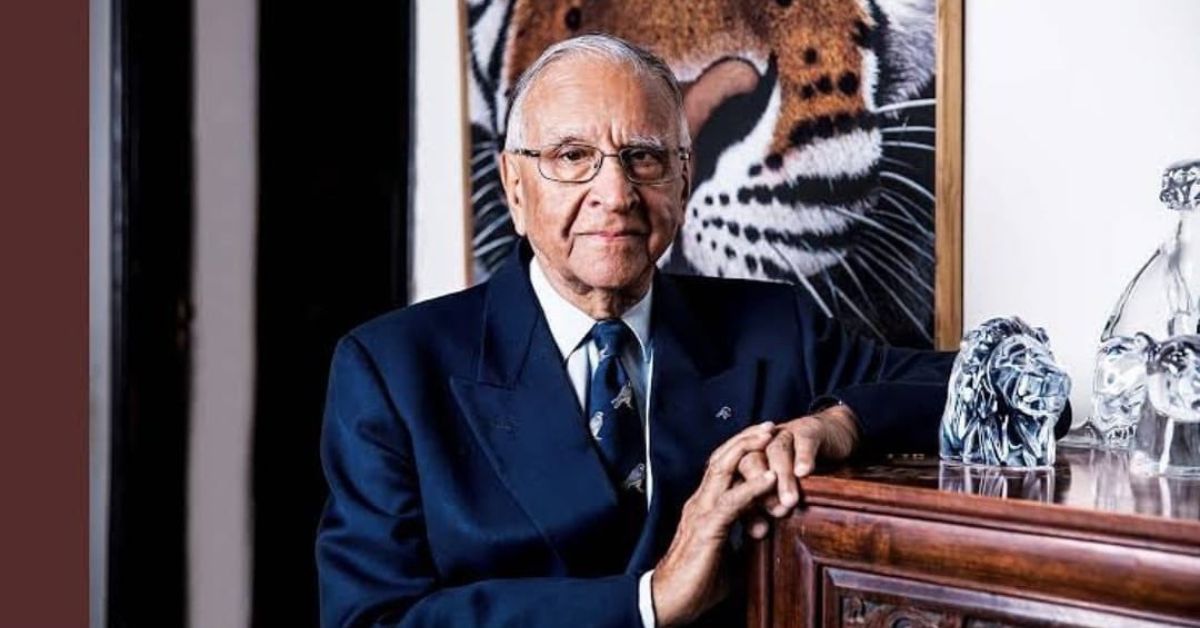

Ex-IAS Officer Who Helped Bring Cheetahs to India For The First Time in 70 Years

Seventy years after the Asiatic Cheetah was declared extinct in India, eight cheetahs were flown in from Namibia to the Kuno National Park in Madhya Pradesh. Meet former IAS officer Dr M K Ranjitsinh, the brains behind the relocation project.

Seven decades after the Asiatic Cheetah was declared extinct in India, eight cheetahs were flown in from Namibia, marking a much-awaited return for the big cat.

On Saturday, Prime Minister Narendra Modi celebrated his birthday with the majestic predators, releasing eight cubs of the African species at the Kuno National Park in Madhya Pradesh.

Another person who was perhaps even happier than the Prime Minister on Saturday was 83-year-old Dr M K Ranjitsinh.

A former IAS officer of the 1961 batch of Madhya Pradesh cadre and among the masterminds of the Wildlife (Protection) Act, 1972, Ranjitsinh dreamt of bringing back cheetahs to the country even as a young boy.

“…I had heard that the last cheetah had been shot and this must have been in either 1948 or 1949. I was an avid reader of wildlife literature and I thought why can’t we bring the cheetah back from somewhere. It was a dream and it’s now come true. I always say the most difficult thing to kill is a good idea,” Ranjitsinh, who belongs to the royal family of Wankaner, Gujarat, told The Indian Express.

While drafting the Wildlife (Protection) Act, 1972, the former director of Wildlife Preservation had included the cheetah as a protected species, even though it was extinct.

The history of the cheetah in India

While there was a time when the cheetah had a robust population across different corners of India, reports suggest that Maharaja Ramanuj Pratap Singh Deo of Koriya shot the last three surviving big cats in 1947. Over-hunting, loss of prey, and habitat loss led to the cheetah’s extinction, which the Government of India officially declared in 1952.

India’s first attempt to bring back the carnivore was in the early 70s. It was Ranjitsingh who spoke to Iran even then, but the negotiations stalled after the declaration of Emergency in ‘75 and the deposition of the Shah of Iran in 1979.

Since then, Ranjitsinh and wildlife conservationist Divyabhanusinh Chavda have worked on the guidelines and policy to reintroduce cheetahs.

The ‘African Cheetah Introduction Project in India’ was born in 2009, but it was only in 2020 that the Supreme Court gave its final approval. The SC appointed Ranjitsinh to chair an expert committee set up for the relocation.

Why Kuno was chosen

Ranjitsinh told Village Square, “In 1981, I went to Kuno and I was struck by the similarity of the habitat. The ruler of Gwalior had selected it as a very suitable area for lions and cheetahs in the 1920s. I declared Kuno as a sanctuary in 1981.”

He added, “When I became the director of Wildlife Institute of India in 1985, I tried again to reintroduce the cheetah, but the numbers had fallen and there was no focus on conservation in Iran.”

Addressing concerns of cheetahs being grassland animals and problems of rehabilitation, the former IAS officer told Village Square that bringing in such predators helps in habitat protection.

“We have learned, not only from the cheetah project, but also from the tiger and snow leopard projects, that bringing in an apex predator has a large cascading effect. It leads to better protection of the habitat — this is most important. Bringing back cheetahs has led to building and protection of the habitat not only for cheetahs but also the prey species. Kuno National Park has seen a spectacular recovery due to the reintroduction of cheetahs,” said Ranjitsinh.

What would this relocation look like?

This is the first time in world history that a cheetah, or any large carnivore, is being relocated from a different continent. As per a statement issued by the Prime Minister’s Office (PMO), Project Cheetah is the “world’s first inter-continental large wild carnivore translocation project”.

Some experts and members of wildlife groups say this project will help increase the number of Asiatic cheetahs, which today only survive in a small population in Iran, wrote The National Geographic.

However, several have also raised several concerns, calling this a ‘vanity project’, premature, and risky.

Since Kuno has a leopard population, there is fear that the cheetahs may be attacked by them. There is also a fear that the cheetahs may stray outside and get killed either by animals or humans.

“It’s putting the cart before the horse. I’m not against the project, I’m against this very tunnel vision thing of just bringing cheetahs and dumping them in the middle of India where there are 360 people per square kilometer,” said Ullas Karanth, emeritus director for the nonprofit Center for Wildlife Studies and a specialist in large carnivores to National Geographic.

Another independent conservation scientist Arjun Gopalaswamy argued that there is no chance for a free-ranging cheetah population now.

“Cheetahs in India perished for a reason, which is human pressure. This has only gotten worse in the 70 years since the species disappeared. So the first question is, why is this attempt even being made?” questioned Gopalaswamy in the National Geographic report.

Meanwhile, Ranjitsingh told Times of India, “I interpret the return of the cheetah as a resolve of both the Indian people and government to let no wildlife species go extinct in the country. If God forbid it does, no effort will be spared to restore it.”

For this former IAS officer, seeing his lifelong dream coming true on Saturday was another feather in his cap.

He earlier won the Lifetime Achievement Award in 2014 for conservation of wildlife. He has also served as former secretary for forests & tourism in Madhya Pradesh; director of wildlife preservation; chairman of Wildlife Trust of India (WTI); director general of WWF Tiger Conservation Programme (TCP); and is presently the regional adviser in nature conservation (Asia & Pacific) for UNEP.

He has also been responsible for saving the central Indian Barasingha from extinction. Ransitsinh also established fourteen sanctuaries and eight national parks in Madhya Pradesh.

Sources

‘The Cheetah in the Forest: A Tribute to MK Ranjitsinh’ by Sanjeev Chopra for First India, Published on 19 September, 2022

‘Seeing the cheetah in Kuno National Park is a dream come true: MK Ranjitsinh’ by Devyani Onial for The Indian Express, Published on 18 September, 2022

‘How cheetahs went extinct in India, and how they are being brought back’ by Esha Roy for The Indian Express, Published on 18 September, 2022

‘Madhya Pradesh: A dream come true for India’s cheetah man’ by P Naveen for Times of India, Published on 17 September, 2022

‘Ambitious plans to reintroduce cheetahs to India’ Published on 22 August, 2022, Courtesy Village Square

‘Inside the controversial plan to reintroduce cheetahs to India’ by Rachel Nuwer for National Geographic, Published on 13 September, 2022

Edited by Divya Sethu, Feature Image Courtesy EarToTheWild/Twitter

If you found our stories insightful, informative, or even just enjoyable, we invite you to consider making a voluntary payment to support the work we do at The Better India. Your contribution helps us continue producing quality content that educates, inspires, and drives positive change.

Choose one of the payment options below for your contribution-

By paying for the stories you value, you directly contribute to sustaining our efforts focused on making a difference in the world. Together, let's ensure that impactful stories continue to be told and shared, enriching lives and communities alike.

Thank you for your support. Here are some frequently asked questions you might find helpful to know why you are contributing?