Why ‘Everyone Needs to Calm Down’ About Bengaluru’s Water Scarcity

Bengaluru water scarcity: From completing projects on time to reviving lakes, constructing open wells, rainwater harvesting and using wastewater as a genuine resource -- experts say the solutions to the city's problem are apparent and eminently doable.

S Vishwanath, a Bengaluru-based water conservation expert — popularly known as ‘Zenrainman’ on social media — believes that national mainstream media reporting on the city’s water scarcity problem has been “completely over the top” and that “everyone needs to calm the hell down”.

“If you define a crisis as a city-level one, the solutions will be found at a city scale. The Government will say ‘We’ll build a large dam on the Cauvery called the Mekedatu and that will bring 3,000 million litres of water a day and solve Bengaluru’s water problem’. But actually, it’s a local problem of aquifer collapse. If we define the problem correctly, we will have the right solutions for the city,” says Vishwanath, speaking to The Better India.

“Incidental stories of people standing in a queue where a borewell has broken down in an RO plant or of some person using wet wipes to wash themselves are not helpful at all. Yes, genuine problems in the city need to be highlighted, but if you chase problems all day with 100 cameras, it’s crazy,” he adds, “This kind of reporting is not helping anyone at all.”

Vishwanath — a civil engineer and urban planner with more than three decades of experience in the water and sanitation sector — has previously worked on the Karnataka Water Policy in 2019. He is also a Trustee of the Biome Environmental Trust, a Bengaluru-based non-profit.

So, how would he define the current crisis?

“Essentially, it’s the failure of the state. If you build your piped water network to the rest of the city, then there will be less pressure on your aquifers, and there will be no need to draw groundwater. Your borewells will have water and there will be no need for tanker water supply. Since you’ve not given piped water supply [to some parts of the city], then the solution lies in groundwater extraction. This means that when groundwater collapses, there is no alternative source of water supply,” he says.

Elaborating on this point further, he says, “There is no [water] problem in about three-fourths of the city. We got 1,470 million litres of water [per day] coming from the Cauvery [river], and there are about 1.1 million [piped water] connections covering 10 people per connection. For 11 million residents of the city, this is not a problem. For 3 to 3.5 million people living in the outskirts dependent on groundwater, there are [water scarcity] problems in pockets.”

Recently the Bangalore Water Supply and Sewerage Board (BWSSB) issued a detailed list marking out areas most severely impacted by water scarcity.

According to data gathered from the Karnataka Groundwater Authority by The Hindu on 29 March, “The data of groundwater levels for last December and this January and February shows that Bengaluru East taluk, which houses one of the major IT corridors of the city, where the water crisis is most severe and groundwater exploitation unbridled, has seen the most dip in groundwater levels this summer.”

So, why are some parts of the city struggling so much with water scarcity?

Vishwanath explains, “It’s the perfect storm. What happened was that we were supposed to get water from the Cauvery Phase-5 project (delivering 775 million litres a day), and that should have been completed a year and a half ago. If this project had been completed, there would have been no crisis. With the completion of this project, millions of people in Bengaluru who don’t have a piped connection would have one with water flowing in it. But that project got delayed and is expected to be completed in May-June 2024.”

“Also, some of the major city lakes have been drained and de-silted. That project should have been completed three years back, but this project has been going on for four to five years. If you desilt and drain lakes for these many years, their capacity to recharge aquifers is non-existent. That’s where all the borewells have dried up,” he adds.

In parts of the city, however, the groundwater table is high, according to Vishwanath.

“For example, in Cubbon Park, the open recharge wells have sufficient water. Some of the lakes, which are full of water, are good for percolation. In these areas, the borewells are at a depth of 150 to 300 feet. Where there is no piped water supply, the groundwater table is very low. If the Cauvery Phase-5 project is completed, the problem of water scarcity in the city will go away to a large extent. If the lakes are filled with rainwater or tertiary treated wastewater, then the aquifers will be recharged and the problem will become a lot less,” he says.

As Vishwanath noted earlier, there are real problems that need to be solved to address water scarcity in the city. In this article, we will highlight these problems and how we can solve them.

Reviving lakes, replenishing groundwater

Whether it’s Chennai, Bengaluru, or Hyderabad, before piped water connections, motorised pumps or electricity could come into play, residents were dependent on surface water.

Now, as a result of rampant urbanisation in the city, lakes have become nothing but recreational and aesthetically appealing water-holding structures where the hydrology or science behind that water body is often forgotten. In many cases, it also happens that throughout the year Bengaluru’s lakes hold sewage, and don’t have space for freshwater anymore. So, when rainfall happens, these lakes are filled with sewage to the brim and are not able to absorb that water.

“All this impacts the lake system, and thereby the groundwater. We are one of the most intense borewelling communities in the world. Nowhere else will you see so many borewells being dug everywhere, which technically depletes all the groundwater reserves,” says Arun Krishnamurthy of the Environmentalist Foundation of India (EFI), which revives water bodies.

“With groundwater reserves depleted and lakes holding sewage, which also means there is no space for freshwater from the monsoon rains to flow into — all these factors put together are causing this kind of drought. Bengaluru isn’t the first though given that Chennai went through something similar in 2018-19. Any urban pocket in India is bound to be affected by such a scenario given that we don’t have a clear understanding of surface water bodies,” he adds.

So, how do you go about revving these water bodies and improving the groundwater level?

Arun speaks of Devanahalli Kere, the first lake EFI took up in Bengaluru for revival in 2022. As an organisation, they have largely focussed on suburban Bengaluru rather than the main city area. This is because the suburban lakes were heading on the current path of the city lakes.

“To prevent any kind of contamination or encroachment, we have taken up water bodies in Ramanagara, Tumkur, and Bengaluru (Rural) districts, and the closest such lake to the main city is the Devanahalli Lake. Within Karahalli, which is next to Devanahalli, we have revived at least five water bodies. What we have achieved is deepening these water bodies to increase storage capacity, regulating their inlet and outlet channels so that there is a free flow of water, and we have also ensured recharge wells have been created in all these systems,” explains Arun.

“Building these recharge wells is all about ensuring there is enough groundwater percolation. Creating a water holding structure based on the soil structure, understanding its utilisation value to the region, and creating percolation trenches and recharge wells have all been our key focus — whether it’s in Devanahalli, Karahalli, the Baddihalli Lake in Tumkur city, or the Hulikunte lake. EFI has restored all these water bodies with this larger point in mind,” he adds.

And the impact of all these initiatives on the communities who live near these lakes has been visible. “Their borewells are not as dry as what we hear from other parts of the city. These lakes, which were often used as dumping sites, are now no longer perceived as such. People want to protect them. When droughts occur, people realise and understand the significance of these lakes better and they volunteer with us to maintain and upkeep them,” he claims.

What goes into the maintenance and upkeep of these water bodies includes the prevention of encroachment, dumping of garbage, and sewage entering that lake, and keeping an eye on the water body in general to maintain its quality and area.

But it’s also important to ensure that the canals interlinking these lakes are well maintained. As Arun notes, “Interlinking of water bodies at an NGO level is impossible simply because between two lakes, the canal system that exists will largely fall under Government land or private land. We can recommend Government agencies to update these canal systems.”

“Our recommendations to the Government will also include properly mapping these water bodies, watershed wetlands, and preventing encroachment where necessary and focusing on the structural integrity of freshwater systems. We desperately need the latter today. But we will not be in a position to revive these interlinking areas completely simply because we don’t have the bandwidth to talk to all the landowners and remove encroachment or more. What is possible on our level, however, is inlet-outlet regulation within the lake’s periphery,” he adds.

Are lakes in the main city beyond redemption?

“They are not beyond redemption if there is a strong political will, heavy scientific backing, and complete community understanding of the problem. Even if one of these elements is missing, these lakes cannot be saved,” he says.

Recharge wells over borewells

Besides lakes, another key element in raising the groundwater level and establishing a surplus water supply is open recharge wells. An open [recharge] well is simply a hole in the ground that allows access to water underground. These wells are used to extract water from the shallowest level — typically found in unconfined shallow aquifers where water is held without any pressure. These aquifers receive water when rain or other surface water percolates down into it — a process known as recharge.

Speaking to The Better India, Vishwanath says, “As we speak, well diggers working with BBMP (Bruhat Bengaluru Mahanagara Palike), as part of the shallow aquifer management project of the Government of India, recently cleaned up a well in a particular locality very close to my house called Nandini Layout. That [open recharge] well today gives one lakh litres of water [a day] and supports 500-700 resident families for non-potable use.”

“In the north of the city, we at Biome Environmental Trust, with the help of a CSR initiative, cleaned up six wells, and in two of them, the women in the area told us not to install a motor. They wanted to draw the water manually. Today 50 to 70 families in the area can draw water from the well. In two other wells, the town municipal council have installed pumps, and so far, they’ve got 70 million litres of water for their town municipal area,” he adds.

Vishwanath goes on to elaborate on other such projects his trust has embarked on.

As he claims, “In the Devanahalli township, where the international airport is located, we’ve been able to work with several NGOs and partners who cleaned up a lake, which is now filled with rainwater and well-treated wastewater from Bengaluru. This water filters into the earth and there is an old open well we have revived. That well gives 2.5 lakh litres of water a day to which we have attached a water treatment plant and are supplying that water to the town of Devanahalli. We have also constructed filter borewells, which are shallow borewells which go 80 to 100 feet deep, and they have a porous casing and function like open recharge wells.”

“Wherever we do good [open] recharge [wells] and lakes are revived, it’s the shallow aquifer which comes back to life,” he adds.

Vishwanath believes that every building in Bengaluru can be part of the solution. “Take all the rainwater you can, store it in a sump tank and reuse it. If you have excess rainwater, please make sure that this goes into recharge wells so that the shallow aquifer is full and then you dip into it in times of need. That’s the overall goal of our ‘One Million Wells for Bengaluru’ initiative.”

So, why weren’t these solutions put in place in parts of the city that don’t have piped connections and are today struggling for water?

“This is because we don’t have a groundwater management plan. We don’t have a groundwater authority which integrates groundwater into our drinking water needs. We just have someone who permits us to drill borewells. We don’t know how much groundwater exists below our feet, where are the recharge zones, where we retain them, how much water are we drawing from each sub-aquifer, and how we draw a balance between demand and supply. In the absence of a groundwater cell in the BWSSB or the absence of a groundwater plan or an aquifer management plan, what happens is everyone is tapping into the aquifer,” explains Vishwanath.

What we are seeing today in Bengaluru is competitive drilling. In parts of the city, people have dug borewells as deep as 1,800 feet.

“Everybody is taking water out. Nobody is putting water back in. Unless we create the right type of institution, which is responsible for groundwater and manages it as a common pool resource for all citizens, this is what will happen and is happening. The problem is institutional and lies in governance or lack thereof,” adds Vishwanath.

If groundwater levels are the problem in the periphery of the main city, Vishwanath advocates the need to move from competitive drilling to cooperative filling.

“Once it’s cooperative filling, we need to fill the lakes and make recharge wells so that when the rains come, the water flows into the aquifer. That is the solution. Currently, we have excellent tertiary treated water in some of our wastewater treatment plants like in Jakkur, Cubbon Park, etc where you can drink the water from the sewage treatment plants (STPs),” he says.

“We need to take this water and fill our lakes quickly, which are now dry, so that the aquifer gets recharged. We should start preparing to clean up our rainwater harvesting systems and make sure new recharge wells are dug so that when the summer rains come, those drops of water are pushed into the aquifer. If this is done, we can overcome the problem in the short run,” he adds.

Harvesting rainwater

The ‘One Million Wells for Bengaluru’ initiative was conceived and facilitated by Biome Environmental Trust to solve the city’s water crisis sometime in 2005. The movement’s main objective has been to enable households across the city to conform to the law mandating rainwater harvesting. And this also includes “a recharge well” option.

Being at the helm of various projects like ‘One Million Wells for Bengaluru’ and other rainwater harvesting initiatives, we asked Vishwanath to explain their impact on the city.

“For example, the Rail Wheel Factory in Yelahanka, where they have done good rainwater harvesting, their open recharge wells are giving them two lakh litres of water a day. At IIM Bangalore, where rainwater harvesting has been done, their borewells are giving them water at 300 to 400 feet, and they’re getting enough water,” claims Vishwanath.

“Wherever rainwater harvesting is done well and in concentrated amounts, there has been no problem. Their aquifers are full and have water despite this year’s drought. Even in Cubbon Park, where people and organisations have done rainwater harvesting like Friends of Lakes, there is water in open recharge wells. Rainwater harvesting can send in X amount of water but your withdrawal should be less than X. If your draw is 2X, then even this won’t help,” he adds.

Having said that, there are more concerns about the rainwater harvesting (RWH) infrastructure in the city. It’s important to note that the BWSSB Amendment Act, 2011, made RWH mandatory for all properties on plots measuring 60×40 sq ft and above, and new properties coming up on 30×40 sq ft sites. In 2015, penalties were introduced for properties that didn’t comply.

In a 7 December 2023 report for Citizen Matters, a Bengaluru-based media publication, reporter Navya PK writes, “…the city currently has 10.8 lakh properties with water connections, but only 1.9 lakh (nearly 18%) of them have implemented RWH.”

“Another 39,703 properties have been identified for non-implementation and are paying penalties every month. These properties include individual homes, apartments (each apartment is counted as a single connection), and commercial properties,” she adds.

In other words, compliance is a serious issue even though installing a RWH system is neither very complicated nor cost-intensive. Vishwanath notes that residents should build robust RWH systems so that they don’t have to face quality-related concerns down the line.

He believes that there are enough quality materials and competent plumbers present in the market. An individual home can install a RWH system for as little as Rs 5,000. Even if you insist on using a high-quality filter, it can be done within Rs 15,000, provided you don’t have to build a new sump, he argues. And the benefits of this system are real.

“In our home, we have rainwater harvesting systems that are operating optimally. Even though the last rains in the city were in November, our 1,000-litre rain barrel still has enough water for our drinking and cooking needs till June,” adds Vishwanath.

On the question of compliance, according to a Bangalore Mirror report by Sridhar Vivan on 9 January 2024, “A staggering Rs 21.24 crore was collected as penalties for non-compliance with rainwater harvesting regulations until November-end last year.”

For non-implementation of RWH in residential properties, fines start from 25% of their water bill for the first three months, and 50% afterwards. For non-residential properties, it’s 50% and 100% of the water bill respectively.

Vishwanath argues that it’s tough to expect 100% compliance and argues that penalising residents may not be the way forward. Instead, he recommends that people should want to set up a RWH system in their homes after a process of education and communication. And the benefits of installing such a system in each Bengaluru home would be immense.

A Bengaluru Water Datajam organised last month by Open City, a civic tech project, found that based on rainfall data from 2022, “456 Million Litres per Day(MLD) could have been harvested in Bengaluru from the rooftops, which is 25% of the water demand of the city – 1890 MLD.”

Is dipping into wastewater the way forward?

Rashmi Kulranjan and Shashank Palur, who are hydrologists at WELL LABS, wrote a column for The Hindu on 24 March 2024 where they identified a solution to the city’s water woes.

“Rainwater harvesting could make a dent on the freshwater needs of the city but it pales in comparison to wastewater. Currently, only one-third of the city’s wastewater is redirected for external reuse, which means it is taken to Kolar, Chikkaballapur, and Devenahalli, where it is used to replenish both groundwater and surface water sources,” they wrote.

“The remaining water flows into lakes and runs off land to join rivers downstream. This means the huge quantum of wastewater generated in the city is an untapped resource. Once treated to the required quality, wastewater can significantly mitigate freshwater consumption and can be crucial in making the city water resilient during low rainfall years,” they added.

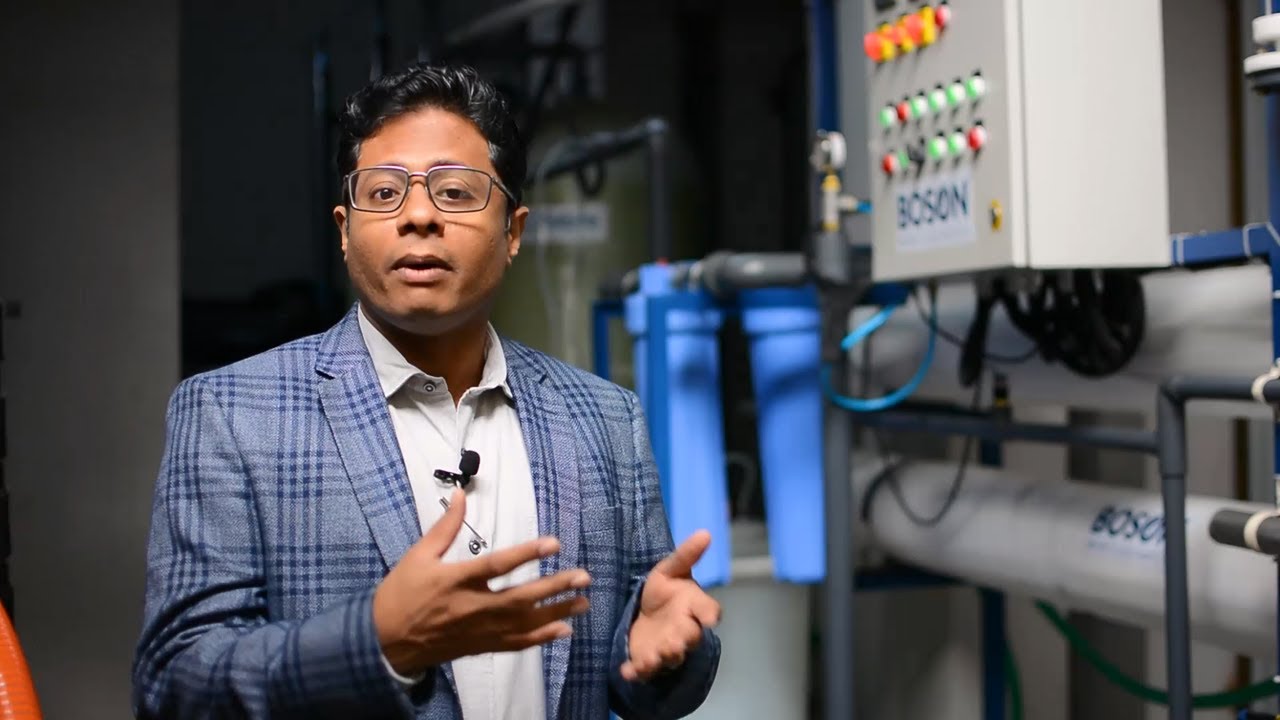

It’s a sentiment that Vikas Brahmavar, founder of Boson Whitewater, a Bengaluru-based water utility startup, shares. Speaking to The Better India, he says, “We should not have a city running on the hope of good rains. After all, if there are no rains till June, it will be a stress even on the municipal supply. We should have a city running on the hope of the wastewater flowing out and employ freshwater supply as a buffer for our everyday needs.”

“In any city in India, when authorities plan water distribution, they never look at what is going out of the city. If you look at developed cities like Singapore, the planning is not based on freshwater available in dams but based on the predictable wastewater which is going out of the city, because that can be estimated clearly based on the population,” says Vikas.

“If the population of a given city is known, authorities in places like Singapore know exactly the amount of wastewater which is going out. From the volume wastewater estimated, authorities can then gauge which industries can be covered by that treated wastewater,” he adds.

In terms of policy, their starting point is wastewater, which addresses sanitation as well as industrial water requirements, and then they look at the freshwater available from dams or other sources.

“This big mindset change has to come. Any developing country should have this mindset of looking at wastewater first before looking at freshwater options,” notes Vikas.

The Boson Whitewater system converts treated wastewater into “high-quality potable water”. The setup has advanced an IoT (Internet of Things), AI (artificial intelligence) and machine learning (ML) enabled 11-step filtration system to reduce physical, chemical and biological contaminants present in STP-treated wastewater. Currently, they work with industries, IT parks, malls, and apartment communities in Bengaluru and Hyderabad, and recycle their wastewater.

At the end of their 11-step filtration process, he claims that the water does not have any contaminants. “E coli, coliforms, heavy metals, high hardness, pesticides, and herbicides are all removed, and the water is crystal clear and potable. National Accreditation Board for Testing and Calibration Laboratories (NABL) certified lab reports indicate the water is drinkable,” he adds.

Essentially, Boson is focused on this enormous volume of water which is going out of homes, apartments, and offices as treated wastewater.

“As per our estimation, a 300-unit apartment will generate about 1,50,000 litres of wastewater a day. The same building complex will have a sewage treatment plant but only 20% (about 30,000 litres) of the treated water that comes out from this facility will be used. In other words, more than one lakh litres of treated wastewater ends up in the drain,” he says.

“Our system can take this one lakh litre of treated wastewater and produce potable-quality water from it so that the neighbouring homes or industrial facilities don’t have to exploit borewell water and instead buy our potable-quality water for whatever they want,” he adds.

Boson Whitewater is currently collaborating with the Bangalore Water Supply and Sewerage Board (BWSSB) on a separate project to address the city’s water scarcity problem. But their prime focus has been the recovery of treated recycled water and selling it.

“Wastewater will always be there whether there is rainfall or not. Since we are recovering high-quality water from wastewater, our clients have not been adversely affected because they have a regular supply which is guaranteed by us on a contractual basis. Some of our clients on rare occasions call in a tanker but for the most part, we’re able to recover the wastewater which is available to the maximum extent and supply that to them,” he says.

(In Part 2, we will look at what residents of Bengaluru can do to mitigate water scarcity in the city.)

(Edited by Pranita Bhat)

(Images courtesy Shutterstock/PQN Studios/Joe Ravi/WESTOCK PRODUCTIONS/MudaCom, S Vishwanath & The Better India)

If you found our stories insightful, informative, or even just enjoyable, we invite you to consider making a voluntary payment to support the work we do at The Better India. Your contribution helps us continue producing quality content that educates, inspires, and drives positive change.

Choose one of the payment options below for your contribution-

By paying for the stories you value, you directly contribute to sustaining our efforts focused on making a difference in the world. Together, let's ensure that impactful stories continue to be told and shared, enriching lives and communities alike.

Thank you for your support. Here are some frequently asked questions you might find helpful to know why you are contributing?