Without Steel Or Cement, This Architect’s Recyclable Homes Will Last A Century!

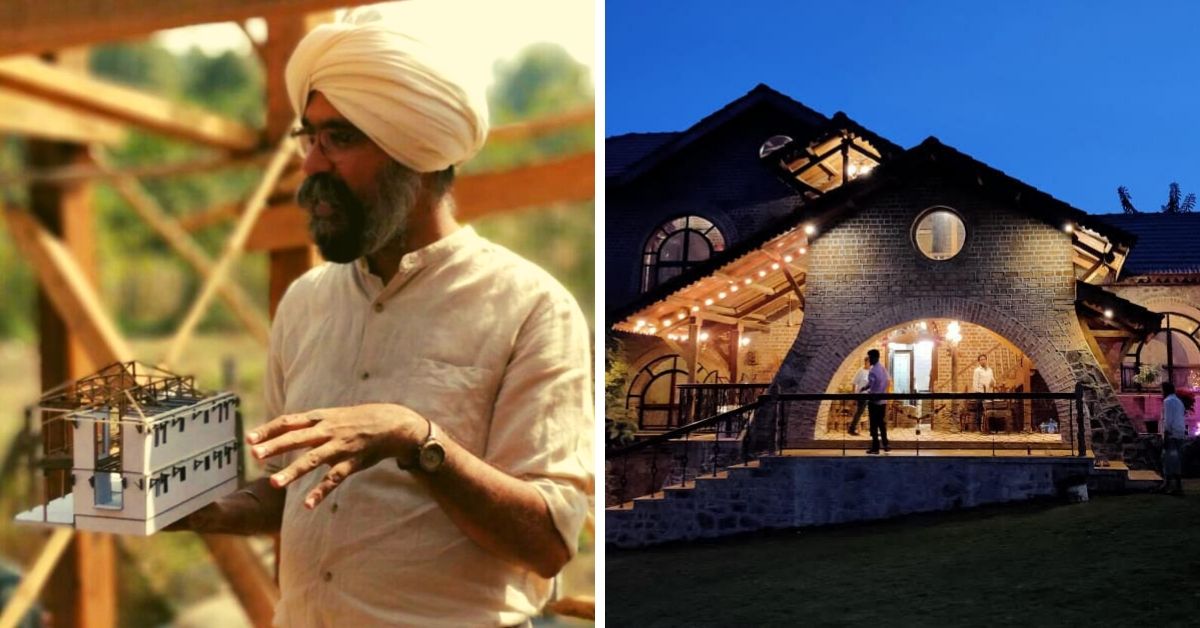

Over the last 17 odd years, Malaksingh Gill's traditional construction materials have reduced carbon footprints by thousands of tonnes.

Here is an exercise renowned architect Malaksingh Gill wants you to do:

You recently moved into a new house made from traditional and sustainable materials like mud, bamboo or wood. You saved a lot on construction costs by using locally sourced materials and employing local masons.

Seventy years down the line, your house stands steady as a rock and if you wish to dismantle your house, all the debris you generate is recyclable and can decompose without hampering the environment.

If this image gave you a sense of satisfaction, then here’s your cue to opt for a house that is durable, damage-free and cost-effective.

“I have always wanted to work for a greater common good and did not fancy the work which conventional architects were doing in Mumbai. As a student, I was critical of how contemporary buildings were not sensitive to the local cultural, and natural environment,” says Mumbai-based renowned architect Malaksingh Gill.

In the last 17-odd years, the 43-year-old has prevented thousands of tonnes of carbon emissions from entering the atmosphere by using traditional construction materials like mud, bamboo, brick, lime and wood to build structures across India.

His projects boast of independent bungalows, community houses to farmhouses.

The Better India (TBI) spoke to Gill to know more about the techniques of sustainable architecture he employs and learn the reasons behind his fascination for eco-architecture.

Finding Inspiration From Anthills, Beehives and Nests

As a student of architecture, Gill always dreamt of creating uncomplicated, budget-friendly sustainable homes perfectly in sync with nature. And Laurie Baker’s low-cost building techniques with maximum efficiency, fired Gill’s imagination.

Known as ‘Gandhi of Architecture’, and the ‘master of minimalism’, Baker offered India and the world a unique architectural tradition blending man and nature.

Once he completed his course from the Rachana Sansad’s Academy of Architecture in Mumbai, he moved to Thiruvananthapuram to work with Baker’s organisation COSTFORD.

“Here, I understood that my teachers were in the fields. My university was in villages, my classrooms were dilapidated buildings and the workshops of the local crafts-persons. All habitats in nature like anthills, beehives and nests motivated me to build sensitively,” he tells TBI.

Underlining the benefits of sustainable homes, Gills says, “I have studied century-old village buildings of various sizes, to validate my argument about their durability, longevity, thermal comfort, bio-sensitivity and cost-effectiveness. Pick any old structure when cement was not available and notice how they still stand the test of time with little or no degradation.”

Gill always eschewed modern architectural techniques like Reinforced Cement Concrete (RCC), steel bars, steel plates, steel mesh as construction material as they cause carbon emissions.

And facts back Gill’s claims on pollution-free or eco-friendly structures. For instance, cement generates around 8 per cent of the global carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions.

Making A Mark

Gill started out when globalisation was booming in India, and issues like climate change were not dinner table conversations.

He entered with ideas of eco-architecture in an arena littered with carbon-emitting construction materials. But it was a risk Gill was ready to take. Gill also had to deal with the high costs of sustainable construction materials in urban spaces.

“When I built my first eco-friendly house in Mumbai, I engaged professional contractors from the city to execute Baker’s set of techniques. I realised that people in smaller towns and villages would not be able to afford the prices of these materials and professional contractors,” he explains.

As a solution, Gill explored the ‘intrinsic’ link houses had with their makers and users in tribal or rural settlements. “I saw an opportunity in the problem; I realised that I need not use the same construction material palette we use in cities while designing buildings in small towns and rural areas,” he adds.

Thus, he began interacting with rural masons and builders, and to his surprise, found a sense of palpable excitement among them to collaborate professionally and improve their skill sets.

An Insight in Gill’s Projects:

For each project, Gill conscientiously follows four basic principles of construction:

- Construction at minimal cost.

- All materials should be from within 1 KM radius around the site of construction.

- Built by the locals.

- Meges with the landscape.

To understand how Gill applied these principles, we list three near-perfect eco-friendly structures he built keeping in mind the local conditions like weather, geography and history:

1) Gill’s First Eco-friendly in Malad, Mumbai

Named ‘Avatar’, Gill made his green architectural debut in Malad, and as per India Today magazine, it was the first eco-friendly house in Mumbai.

Well aware of the city’s shrinking spaces, the house is compact but efficient in design.

The stone and brick walls match the unique design of the spiral staircase made from treads of wood and stone. Brick corbels support the treads, while counterweights provide additional support from outside.

![]()

Brick jalis fitted with glass bottles provide indirect lighting and a stained glass effect, lending a distinct aesthetic to the spaces.

Using cross-ventilation to his advantage, Gill has provided built-in seats near the windows.

2) A Green Community House in Karjat

Gill addresses this project as ‘unique and inclusive’. It is built in the middle of a natural forest.

Gill employed the tribal inhabitants of Karjat for construction work who underwent a workshop on eco-friendly technology. He incorporated the knowledge and skills of the locals into the design and execution stages.

The architect gave utmost importance to the use of natural light due to the lack of power in the 60-acre forest.

The masons laid the foundation of the house in random rubble stone with mud mortar and built the plinth or lowest part of the house on a slope that helped with soil retention.

The masons mud prepared the mixture of cob and mortar in the pit with bare feet as it is the least damaging process to the environment. It neither involves any processing of the mixture, nor outsources the material as mud was readily available within the site limits.

Gill chose to use the extremely durable Kadappa stone lintels for openings and for storage purposes.

“For an Adivasi dwelling and a community living centre, an important part of the brief was to provide as much storage as we can. This was achieved by putting horizontal Kadappa stone shelves at different heights throughout the structure,” reads the feature of the community house.

3) Integrating Regional Features

Gill built two bungalows with a common pol or courtyard, an intrinsic to Gujarati houses. It is built with brick masonry in lime mortar, with an R.C.C. filler slab.

A series of segmental arches connect private living rooms to the pol, thus ensuring passive lightning and ventilation in Vadodara’s dry climate.

Meanwhile, the brick jalis fitted with glass bottles provide indirect lighting and a stained glass effect which is another feature of traditional pol.

From Finding Inspiration to Becoming One

Gill believes in passing knowledge as the ultimate goal of the learning process.

For the same, he gives lectures in architectural colleges and most of his teaching process is outside the classroom. Based on his observations, he offers deserving students a place in his team.

“This is my way of spreading the work which I believe can bring a constructive difference in society through architecture. Today, many of my students are teachers, practising in villages, and winners of awards at many levels,” he shares.

Architecture couple Dhruvang Hingmire and Priyanka Gunjikar were in their fourth year when they visited Satara in Maharashtra to study the regional architecture along with their professor, Malaksingh Gill.

There they visited an old lady’s house built entirely from mud and cow dung plaster. Adding colour and aesthetics to the house, were the bangles she had embedded into the walls.

This inspired the duo to make their career in sustainable architecture and even worked with Gill for three years before starting their independent company.

Read about the couple’s cement-free breathable home.

“Malaksingh sir always emphasised on how knowledge is overrated. True wisdom is to have the humility to always keep learning from everyone around you – especially from the often neglected vernacular contexts around us. He is beyond just a teacher who teaches a particular subject, about material or technique. His teachings transcend even the subject architecture – and are a huge support in everyday life,” Dhruvang tells TBI.

With ‘sustainability’ a war cry against environmental degradation, architects like Gill are true warriors bearing the flag of eco-living high.

Get in touch with him here.

Also Read: Jaalis, Baolis & More: Architect Couple Uses Ancient Designs to Make Sustainable Buildings!

Image Credits: Malaksingh Gill

(Edited by Saiqua Sultan)

Like this story? Or have something to share?

Write to us: [email protected]

Connect with us on Facebook and Twitter.

If you found our stories insightful, informative, or even just enjoyable, we invite you to consider making a voluntary payment to support the work we do at The Better India. Your contribution helps us continue producing quality content that educates, inspires, and drives positive change.

Choose one of the payment options below for your contribution-

By paying for the stories you value, you directly contribute to sustaining our efforts focused on making a difference in the world. Together, let's ensure that impactful stories continue to be told and shared, enriching lives and communities alike.

Thank you for your support. Here are some frequently asked questions you might find helpful to know why you are contributing?