This Eco-Warrior Reforested 400 Acres of India’s Oldest Mountains with Native Flora!

The land lay barren save for the invasive Vilayati Keekar that prevented native trees from growing. Thanks to Vijay's efforts, the range is today a self-sufficient ecosystem of over 200 plant species that needs no human intervention!

Nearly 400 acres of the oldest mountain range was aching with an exploitative human activity until 2009. The Aravalli ranges, extending from today’s Delhi in the North to Gujarat in the West, formed when the Indian plate separated from the Eurasian plate during the Proterozoic aeon. These ancient ranges, which are the lungs of the states of Delhi, Haryana, Rajasthan, and Gujarat, were facing excessive exploitation since the early 1980s.

Several mining pits and stone-crushing zones in the Aravalli Biodiversity Park also contributed to the air, water and soil pollution.

It was only in 2002 when the Supreme Court put a ban on the mining activities that the 378 acres were given some respite. However, it took the authorities another seven years to come up with a plan for the land and implement it.

In 2009 IAmGurgaon (IAG) proposed to make a biodiversity park in the mined site. IAG, a citizen-driven initiative was launched to restore the long lost greenery in 2009.

You can read in detail about their initiative here.

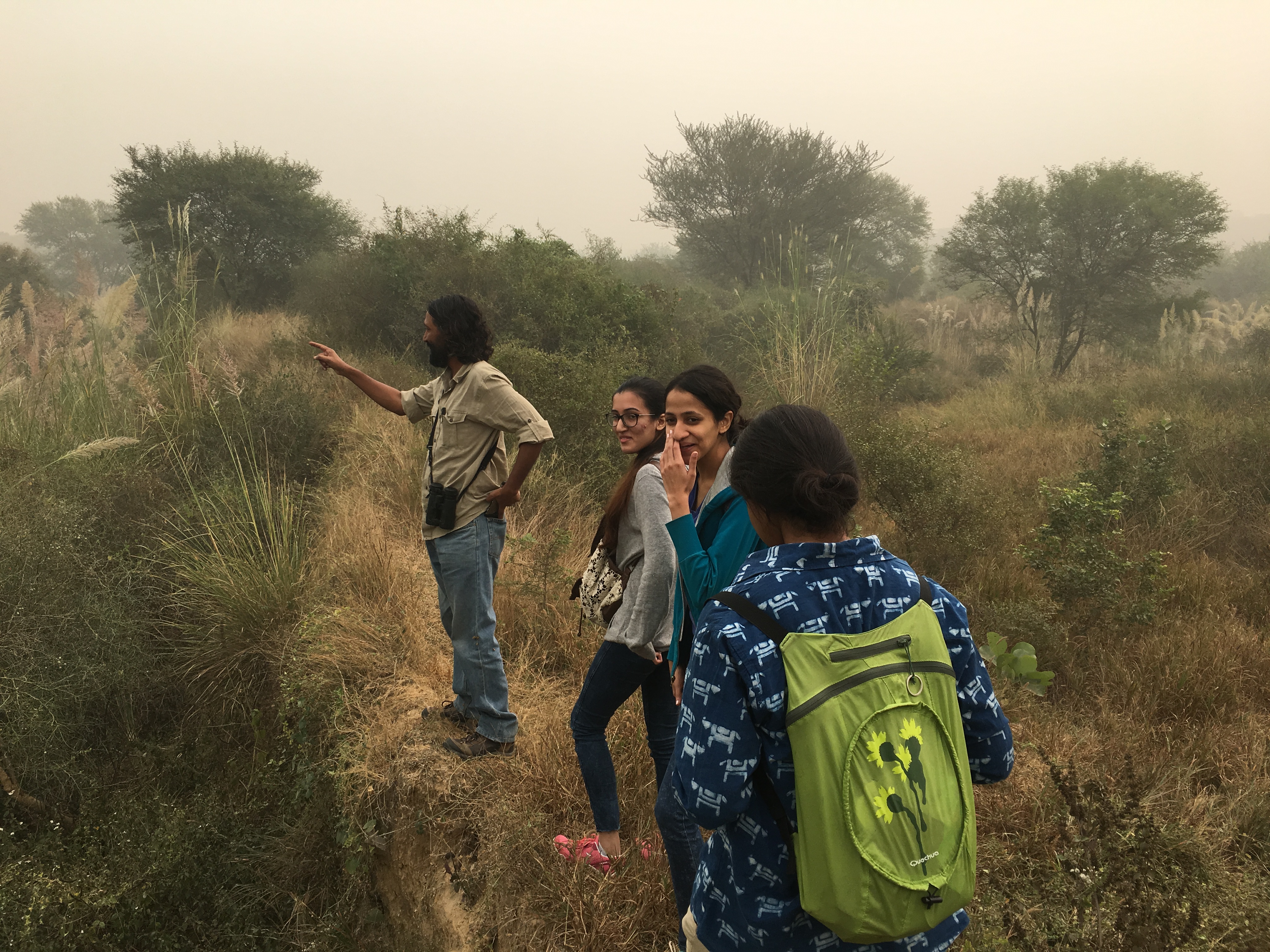

To aid the initiative, the citizen group consulted Vijay Dhasmana, an eco-warrior, who had a brilliant sense of flora and fauna. Together, they undertook a massive project to plant rewild the mining site into the Aravalli forests.

Speaking to The Better India, Vijay explains, “The land where the group wanted to plant was a 40-year-old mining site. It had been declared as the Aravalli Biodiversity Park. There were several mining pits, fortunately, the groundwater was not exposed. Land, by and large, was hilly with rocky outcrops of quartzite rocks, mostly gravel in the form of soil. In some patches, there was old alluvium deposit. There was hardly any vegetation on the land, as fire and grazing pressure was huge. Whatever greenery you saw was because of Vilayati keekar (Prosopis juliflora) an Alien Invasive Species (IAS) brought from Central America and used extensively to green the Delhi Ridge in the early 20th century.”

Often, afforestation is equated to greening and used very casually. Our general approach is that we plant trees irrespective of their nativity, they could be from America or Australia, and make an area wooded. We don’t realise that such a collection of trees is not sustainable. Our approach to greening or afforestation should be to create habitats, which will regenerate and propagate themselves.

Allow me to elaborate.

Increasing green cover in an area implies that it be sustainable and nurture an ecosystem that thrives within that area.

This involves insects, birds, animals, shrubs, trees and grasses. The process to begin growing the forest begins, literally, at the grassroots level.

While the saplings of native trees take their own time in growing, it is the native shrubs and grasses that not only protect the soils but also invite insects. Once the shrubs and grasses start flowering and fruiting, insects diversity and populations increase; birds come to feed on them, they pollinate and disperse the seeds. One thing leads to another, and eventually, an ecosystem is generated, a wheel of regeneration is turned.

This ecosystem can be as miniature as your garden or as massive as a 400-hectare forest.

Vijay wanted to ensure that their project would nurture all forms of wildlife, native to the Haryanvi area of Aravalli. This had to begin with planting native species of plants.

“The misconception about afforestation is afforestation itself. The biggest threat today is loss of land where forests were. We are losing our wilds very fast. They are being degraded, fragmented through roads, and severely under pressure,” Vijay says.

He adds, “Firstly, if you have to plant, you should plant trees native to the particular region.

The Aravallis is a very complex ecological system. What we see of it today is more than three billion years old. They have shaped the landscapes of the Western and Central India.”

The very first step for the team was to compile a list of plants native to the area. Plants like the Prosopis Juliflora (locally known as vilayati keekar) had infested the area. This shrub belongs to Mexico, South America and the Caribbean, but its colonisation was so vast in the Aravalli that people had become more familiar to it than the actual native species.

Vijay decided that this green drive needed to begin with clearing the area off the vilayati (foreign) keekar and planting of species like dhau, dhak, ronj, bistendu and karonda, instead.

What was wrong with the planting of vilayati keekar that was grown in Haryana for decades?

For one, this “colonising” plant does not allow the growth of other species around it, through a process called allelopathy. It exploits the nutrients from the soil and provides almost nothing to the birds and animals. Perfectly suited for a South American climate and geography, the vilayati keekar is an invader in Haryana.

So, Vijay and his team started studying historical records about the flora in that part of Haryana and Delhi.

Speaking to the Earthy Matters, he said, “I haven’t got any academic training in rewilding or even in plants for that matter. It is simply common sense. It’s not rocket science. What it definitely needs is understanding where to look. In the case of the Aravalli Biodiversity Park, we had records of forest-kinds recorded during British times. After that, in the 60s, there is someone called Maheshwari, who came out with the Flora of Delhi. So, there are books that talk about the flora that exist in different landscapes. You pick up from there and do the groundwork and say, these are the species Parker is talking about or Maheswari is talking about or somebody else is talking about. Then you go around the landscape and check the species. Then you compile your list…the candidate lists for the landscape.”

Also Read: Teacher Lives in Forests For 20 Years, Uplifts One of Kerala’s Most Underprivileged Tribes!

Once the list was ready, Vijay and the IAG got down to work.

For the next ten months, it was all about making trips to collect seeds from Rajasthan and other places where those seeds could be sourced for the nursery.

They began with germinating plants in the nursery; 35 species in the first year, 58 species in the second, then another 85, 130, and finally, 160 other species of plants native to the Aravalli forests. Today they have added 200 plant species native to Aravalli to the park.

Drip irrigation systems were installed so that very little water was wasted. In fact the water came from the nearby STP plants. Irrigation was done up to three years, after which plants were strong enough to bear the brunt of the climatic conditions.

The landscaping of the plant species was done after thoroughly studying the topography of the area and comparing the needs of plants.

“The land had few patches of Vilayati keekar and otherwise mostly barren. Today, it has distinct micro-habitats or forest types, such as Salai (Boswellia serrata) forest, Dhau (Anogeissus pendula) forests, Dhak (Butea monosperma) forests, Kaim (Mitragyna parviflora) valleys, Khair (Acacia catechu) forest, Babool (Acacia nilotica) forest patch and Saccharum and Pheonix habitats,” the eco-warrior says.

He adds, “We are seeing that these species have started flowering and fruiting and showing regeneration. It gives us hope that these habitats are going to be sustainable in the long run. Most importantly, they are most suitable for our climates and don’t need any extra inputs in the form of fertilisers or water. It has also become a safe habitat for birds and animals.”

You May Also Like: 1 Cr Trees, 2500 Check Dams: How a Determined 86-YO Transformed 3 Gujarat Districts

As time passed, IAG also assigned gardeners to maintain the plants. You know what they say, one must take care of a plant for the first three years, after which it will take care of itself for life.

That is exactly what happened in the case of the Aravalli too. Some species perished, some thrived but the forest as a whole started growing.

Insects lured birds—common and rare species and eventually, mammals too made an entrance into the massive biodiversity park.

Today, the lush forest has been serving Haryana as its green lung. Although it still faced some challenges like the National Highway Authority of India (NHAI) proposing to build a road through it, citizens ensured that their green cover remained untouched by any external hindrance.

A perfect example of how active citizen initiatives can save India or at least some of its vulnerable parts, Vijay and the IAG team have pioneered a fantastic example of dedication and informed labour for our forests.

(Edited by Shruti Singhal)

Images courtesy: Vijay Dhasmana

Like this story? Or have something to share? Write to us: [email protected], or connect with us on Facebook and Twitter.

If you found our stories insightful, informative, or even just enjoyable, we invite you to consider making a voluntary payment to support the work we do at The Better India. Your contribution helps us continue producing quality content that educates, inspires, and drives positive change.

Choose one of the payment options below for your contribution-

By paying for the stories you value, you directly contribute to sustaining our efforts focused on making a difference in the world. Together, let's ensure that impactful stories continue to be told and shared, enriching lives and communities alike.

Thank you for your support. Here are some frequently asked questions you might find helpful to know why you are contributing?