A Freedom Fighter’s Idea Revolutionised India’s Rail Travel Making it Comfortable for Millions

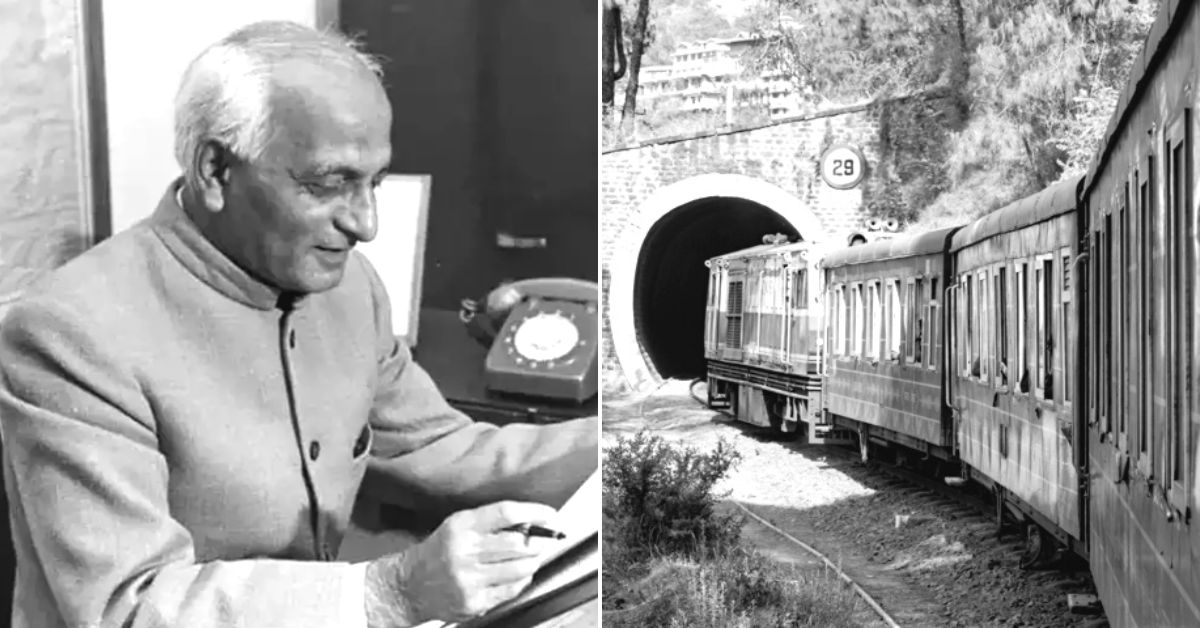

On his 100th birth anniversary, we remember Madhu Dandavate, a freedom fighter inspired by Mahatma Gandhi who fought for the liberation of Goa, took on the Emergency and improved rail travel for millions with his idea.

In a 2005 column for The Hindu, historian Ramachandra Guha argued that since the dawn of Independence, there are only a few Government of India ministers who “shall be remembered for having carried out programmes that radically reshaped the lives of their people”.

Guha listed Sardar Vallabhai Patel, who as home minister between 1947 and 1950, carried out the integration of the princely states, “thus altering the politics and geography of modern India”. Next, he listed Manmohan Singh, who as finance minister between 1991 and 1996, “dismantled the licence-permit-quota-raj, thus altering the economy and society of modern India”.

After Vallabhai Patel and Manmohan Singh, Guha listed the name of Madhu Dandavate — a physicist, freedom fighter, and socialist leader from Maharashtra — who as railway minister in the Janata Government between 1977 and 1979 “put two inches of foam on what passed for ‘reserved sleeper berths’ in the second-class sections of trains”. Although a simple intervention, this initiative had a profound influence on the lives of millions of ordinary Indians.

As Guha argued, “Before 1977 (the year Dandavate became railway minister), there was an enormous difference between the first-class, where the berths were padded, and the second-class, where they were made of hard and bare wood.”

“If you were lucky enough to travel up front, you slept well; otherwise you woke up with a painful back and (were it winter) a cold in the head as well,” he added.

Today, the Indian Railways carries approximately 23 million passengers daily from nearly all strata of society. Dandavate’s decision to introduce these two inches of foam was driven by a desire to assist the country’s poor in a practical way. As he once famously argued, “What I want to do is not degrade the first class, but elevate the second class”.

As railway minister for those two years, those two inches of foam were put in place across the major trunk lines. The first train with these safer and more comfortable seats was flagged off on 26 December, 1977, between Mumbai and Kolkata (and back). Even though the Railway Board wanted to call this train the Eastern Express, Dandavate decided on the name Gitanjali Express, inspired by Rabindranath Tagore. The train even had portraits of the Bengali poet hung inside it.

As Guha wrote, “Once the process was begun it could scarcely be stopped. By the end of the 1980s, all trains of the Indian Railways had these padded berths in their second-class compartments. By now the change has helped hundreds of millions of people. If a social history of the Indian Railways is ever written, it might be divided into two parts, these entitled ‘Life before Dandavate’ and ‘Life after Dandavate’.”

Besides this initiative, he also introduced the computerisation of railway reservations “to curb corruption” and “streamline the procedures”. As he noted in his Railway Budget speech for 1978-79, “To streamline the mammoth and complex operation involved in the matter of reservation of rail accommodation in trains and to eliminate malpractices, I am also considering computerisation of passenger reservations in the four metropolitan cities.”

He also repaired the relationship between the Indian Government and railway unions that had suffered during the strike of 1974 and was suppressed by the Indira Gandhi Government.

A man of his time and ahead of his time, Dandavate lived a remarkable life in the public eye.

Inspired by Gandhi

Born on 21 January, 1924, in Ahmednagar, Dandavate completed his MSc in Physics from the Royal Institute of Science, Mumbai, following which he went on to head the physics department at Siddhartha College of Arts and Sciences, Mumbai. His entry into politics, however, was inspired by Mahatma Gandhi during the tumultuous Quit India Movement in 1942.

Similar Story

India’s First General Election & More: 8 Iconic Pictures Capturing Indian History

NA

Read more >“As a young college student, I was present at the Gowalia Tank Maidan (August Kranti Maidan), in Bombay on the morning of 9 August, 1942, because it was announced that the national flag would be unfurled there,” wrote Dandavate in his book ‘Dialogue with Life’.

On the previous two days, the All India Congress Committee (AICC) held a session at this very venue where Mahatma Gandhi had issued the clarion call for ‘Quit India’.

“I was in the Royal Institute of Science. I heard the speech delivered by Mahatma Gandhi at the Congress session in 1942. I was in college when the call given to the people was ‘Do or Die’ and the warning given to the British was ‘Quit India’,” wrote the Independence activist.

“Mahatma Gandhi wanted his message to be heard all over the world, so he delivered his speech both in Hindi and English. I was present as a visitor in that session and was deeply moved and inspired by its proceedings,” he added.

Beyond Gandhi, however, he was also deeply inspired by the ideals of the Congress Socialist Party. Its leaders — including the likes of Jayaprakash Narayan, Ram Manohar Lohia, and Yusuf Meherally — played a pivotal role in shaping his politics.

Following Independence, these socialist leaders quit the parent Congress party, providing a strong and principled opposition to Jawaharlal Nehru. Dandavate followed their lead in this regard.

Satyagraha for the Liberation of Goa

Although Goa was freed from the clutches of Portuguese colonial rule and joined the Indian union only on 19 December, 1961 (following military action by the Indian Army), many leaders — including the likes of Dandavate — performed courageous acts of Satyagraha marked by nonviolent protests to put pressure on the Indian Government to act.

As secretary of the Goa Vimochan Sahayak Samiti (Goa Liberation Aid Committee) in Mumbai, he bravely led a group of 93 people to launch a Satyagraha at Netarda (a small village on the border of Goa) and paid a pretty heavy price for it.

As he wrote in his book ‘Dialogue with Life, “Normally when the Satyagraha was announced, the police were posted on the border, but we walked about 7-8 miles beyond the Portuguese border, raising slogans. I had the national tricolour flag in my hand.”

“The Portuguese police came. They were well-armed. We were stopped. I was in the front and was asked to hand over the flag. I refused to do so. We had come here to hoist this flag in the Goan territory, and I would not surrender it. They beat me and after an intense struggle, they took away the flag. We were asked to return but we did not budge,” he added.

Backed by slogans like ‘Nahin, nahin, Kabhi nahin, Bharat Goa alag nahin’ and ‘Lathi, goli khayenge, phir bhi Goa jayenge’, he took on the might of the Portuguese colonial police as they began a lathi charge on all satyagrahis and beat them with the butts of their rifles.

“They beat me till I fell unconscious. Strangely enough, even after I became unconscious, they trampled on my back with their military shoes. After a while, my colleagues took me to the Military Hospital at Belgaum and then to Bombay. They found that my hip joints were injured very badly and I had to be given infrared rays for that injury. My strong young bones could take the torture then, but later on, after many years, it was diagnosed that my hip joints had totally degenerated and the replacement of these joints with metallic plates and rods was the only solution. At present I have two stainless steel plates and two metallic rods in my body,” he wrote.

It was really a brutal episode as far as police action is concerned. In the past, the police would usually just arrest the satyagrahis and take them to jail. But the satyagrahis made their point.

Writing on the impact of this Satyagraha action, he noted, “I feel proud to say that it did generate a climate to pressurise the Indian Government leading to the military action to liberate Goa. There was hardly any resistance during the military action. My feeling is if this military action had been taken earlier, there would not have been so much sacrifice and death. Our Satyagraha in 1955 did create a spirit of resistance against Portuguese rule in Goa.”

Taking on Indira Gandhi’s Emergency

Like many of his socialist peers, Dandavate challenged the Indira Gandhi administration’s proclamation of Emergency (1975 to 1977) — a dark period in our history marked by the usurping of basic civil rights and democracy — and served many stints in prison as a result.

Witnessing the inhuman treatment meted out to political prisoners, particularly his colleague and socialist leader Mrinal Gore, Dandavate shot off a letter to Indira Gandhi from prison.

“I am quite conscious of the consequences of this letter. I can well imagine that through this communication, I am likely to incur your wrath and get my detention prolonged. However, I feel least worried about it. I will remain completely undeterred even if the prison yard from which I write this letter were to become my graveyard,” wrote Madhu Dandavate in a letter dated 14 January, 1976, to the then prime minister Indira Gandhi during the Emergency.

He signed off this scathing letter to the then-prime minister by declaring his undying will to resist. “Rest assured that in this land of Mahatma Gandhi, my will to fight for freedom will ever remain more powerful than the engine of repression that seeks to suppress it,” he wrote.

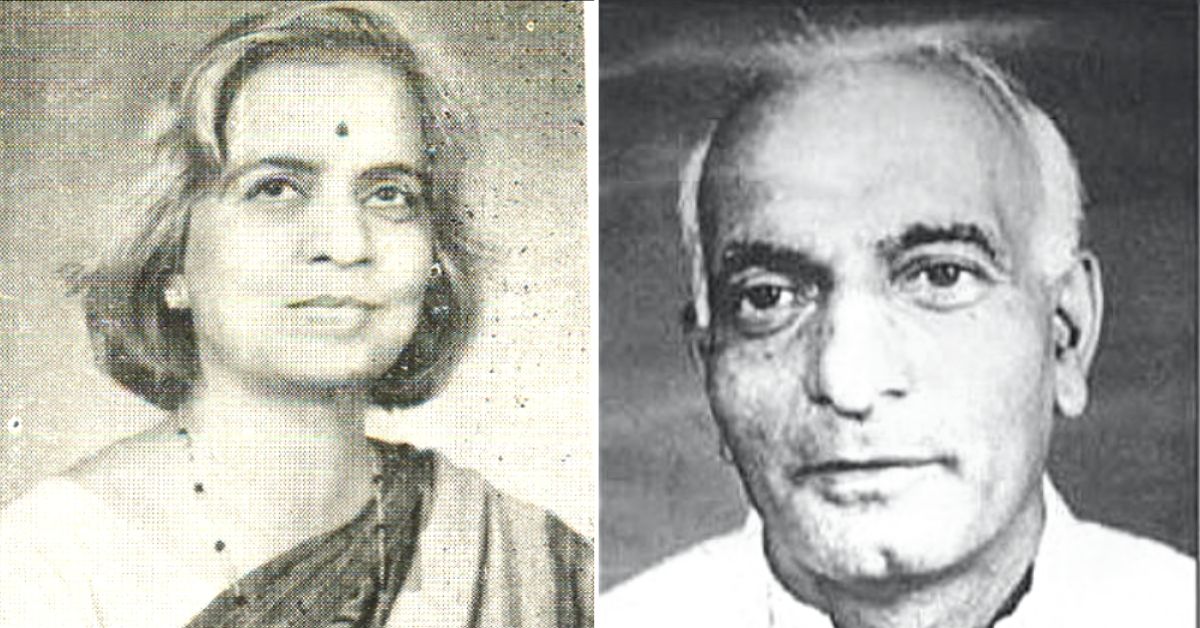

Dandavate, however, is also famously known for his series of letters from jail to his wife Pramila, a legendary socialist activist in her own right, who was also imprisoned during the Emergency.

After nearly 23 years of marriage, the couple were suddenly split apart by a distance of over 800 km. As products of the freedom struggle, avowed socialists and seasoned activists, the Government arrested Dandavate on 26 June, 1975, and subsequently picked up Pramila on 17 July, 1975.

During their time in prison, the only way they could correspond was through letters. The couple exchanged nearly 200 letters, where they discussed, among other things, music, poetry, books, philosophy and politics. More importantly, however, their letters were a testament to how the love they shared for each other translated into resistance against an authoritarian regime.

“The letters register the pain of separation as well as how they worked through it to reaffirm their emotional bond by restating their commitment to freedom….They loved each other because they loved freedom. Their love also enriched and extended the meaning of freedom,” wrote scholar Gyan Prakash in Emergency Chronicles: Indira Gandhi and Democracy’s Turning Point.

Leaving behind a legacy

Dandavate had a long and remarkable career in politics — serving as a five-time Member of Parliament from the Rajapur constituency of Maharashtra, finance minister in the VP Singh government (1989-90), and deputy chairman of the erstwhile Planning Commission in 1990, and again from 1996 to 1998. His parliamentary career came to an end after losing to a Congress candidate in 1991, following which he slowly moved away from national politics.

After battling cancer for a protracted period, Dandavate passed away in Mumbai on 12 November, 2005, at age 81. As per his wishes, his body was donated to the city’s JJ Hospital.

From fighting for India’s freedom to Goa’s liberation from the Portuguese and impacting the lives of millions as a union minister and parliamentarian, Dandavate represented the best of us.

(Edited by Pranita Bhat; Images courtesy X/Asia Society India Centre and loksabha.nic.in and Shutterstock)

Sources:

‘Two Inches of Foam’ by Ramachandra Guha, Published on 20 November 2005 by The Hindu

‘Dialogue with Life’ by Madhu Dandavate; Published on 11 March 2005 by Allied Publishers

‘Speech of Prof. Madhu Dandavate Introducing the Railway Budget for 1978-79, on 21st February 1978’ courtesy Indian Railways

‘A moral compass’ by Ramachandra Guha; Published on 13 January 2024 courtesy The Telegraph (online)

‘Emergency Chronicles: Indira Gandhi and Democracy’s Turning Point’ by Gyan Prakash; Published on 28 November 2018 courtesy Penguin Viking

If you found our stories insightful, informative, or even just enjoyable, we invite you to consider making a voluntary payment to support the work we do at The Better India. Your contribution helps us continue producing quality content that educates, inspires, and drives positive change.

Choose one of the payment options below for your contribution-

By paying for the stories you value, you directly contribute to sustaining our efforts focused on making a difference in the world. Together, let's ensure that impactful stories continue to be told and shared, enriching lives and communities alike.

Thank you for your support. Here are some frequently asked questions you might find helpful to know why you are contributing?