‘We Ended the Dancing Bear Practice & Rescued 3,000 Families From Abject Poverty’

Geeta Seshamani narrates how along with Kartick Satyanarayan and the team at Wildlife SOS they sort to break the cruel Dancing Bear practice by the Kalandar community that used sloth bears as a source of earning.

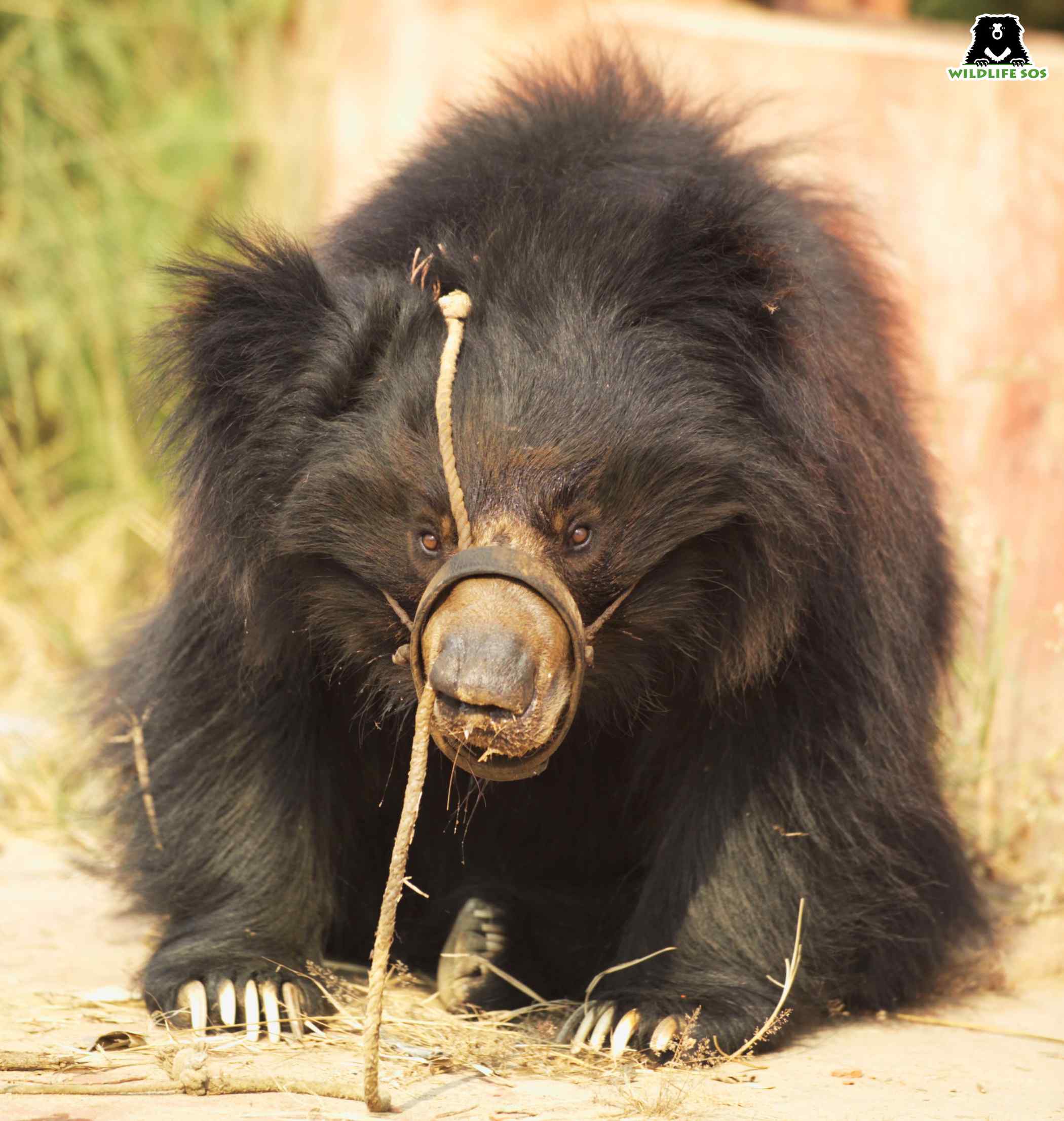

In 1995, Geeta Seshamani witnessed a sloth bear bobbing up and down in the middle of the Delhi-Agra highway. “The poor bear was being dragged along by a coarse rope that was threaded through his bleeding and infected muzzle while his ‘owner’ begged money off the tourists,” she says, with anguish in her voice.

The horrific practice of the Dancing Bear—as it was referred to since the bear jumped up and down in pain when their handlers (from the Kalandar community) tugged at the rope—struck a nerve with Geeta. It involved piercing a hot iron rod into the soft muzzle of the bear cub, after which a rope is threaded through it, which is then used to make the bear ‘dance’.

The dancing bear act began around 400 years ago when a nomadic community entered India from Persia and performed tricks to entertain Mughal emperors. Over the centuries, the emperors and kingdoms disappeared, but the ‘dancing’ bear trade remained. This transitioned to cheap street entertainment for tourists. While the practice was made illegal in India in 1972, underground trafficking of the bears still took place.

“I realised this was not just entertainment for tourists but torture and abuse of an endangered wild animal that was being exploited for human greed,” says the co-author of ‘Dancing Bears of India’ and ‘Trade in Bears and Their Parts in India: Threats to Conservation of Bears’.

Since then, Geeta, her old friend Kartick Satyanarayan, and their team at Wildlife SOS have rescued 628 bears. They have rehabilitated the bears and helped provide alternative livelihood options to the Kalandar community — who traditionally captured the bears.

Life At The End of A Rope

The child of a military father, Geeta travelled to many places while growing up. She completed her education at Delhi University and said that she has always been compassionate about animals.

“What I recall as a ‘life-changing incident’ was when I was 20 and saw a dog in pain, after having met with a road accident. The accident had happened right in front of my eyes, and the human responsible had not bothered to glance back. I immediately leapt out of the car, picked the dog up, and took it to the side of the road. Unfortunately, the injuries were fatal, and the dog passed away on my lap,” the 70-year-old laments.

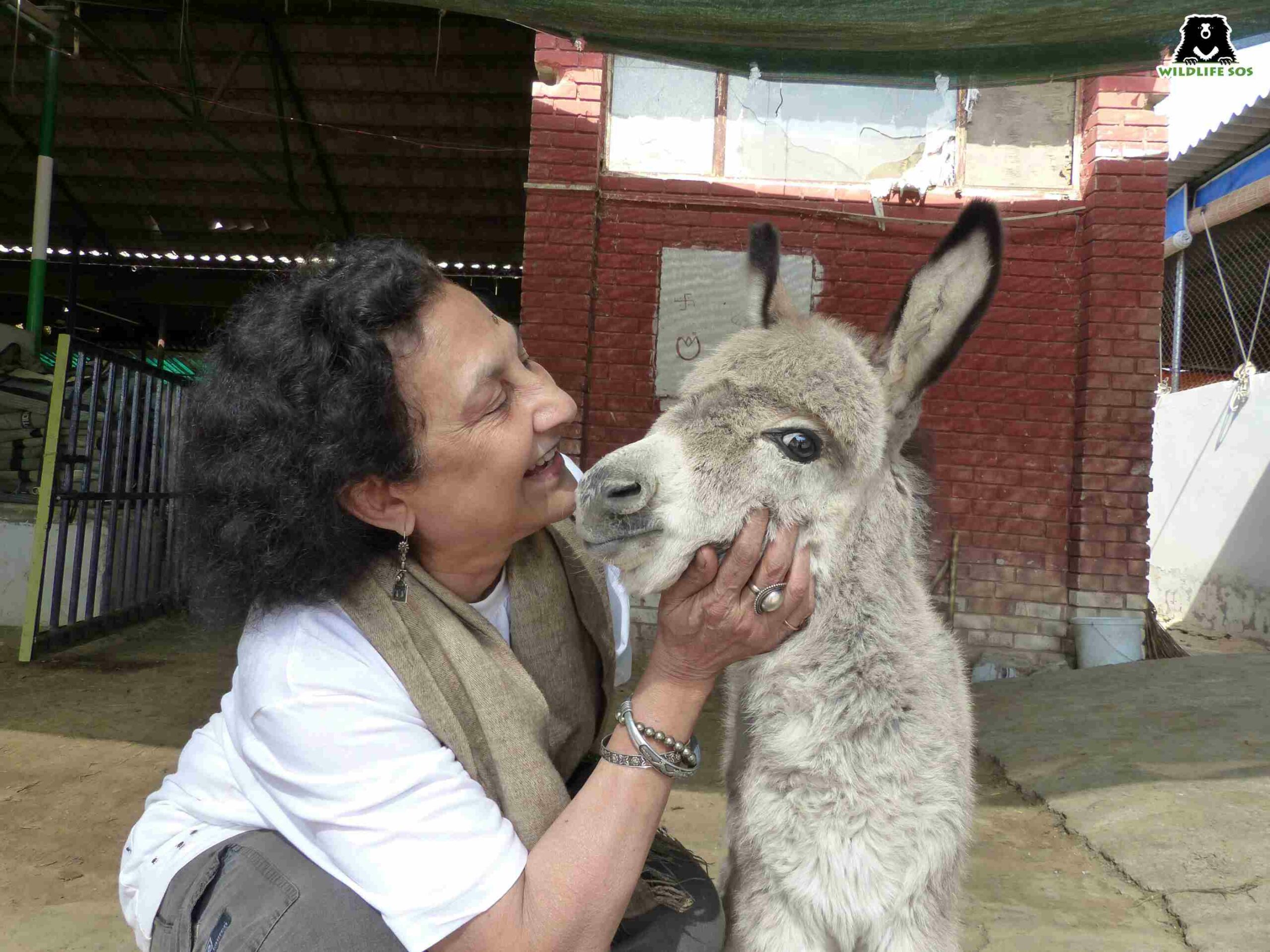

This incident compelled her to become a voice for the voiceless and create an institution that would help such animals in distress. “In 1979, I met a group of school children who were part of a ‘kindness club’ led by Anuradha Modi. Friendicoes SECA (Society for the Eradication of Cruelty to Animals) is one of the oldest animal shelters in Delhi-NCR,” says Geeta who is now the Vice President of the organisation.

Later, in 1995, she and Kartick established Wildlife SOS that runs several projects to support wildlife conservation in India.

In an earlier interview with The Better India, Kartick also admitted to finding his calling early on when he saw large-scale poaching of wildlife and habitat destruction was doing irreversible damage to ecosystems.

After witnessing the bear in 1995, Geeta went with a filmmaker to a village of the Kalandar community, just 30 km outside Delhi, to find a horrifying reality.

“The bears were tied to sticks and Tikar ka ped. They were lying in dirty conditions with swarms of flies around them. And that night that I stayed with them was a life-changing experience. I saw the poverty of the people. The children were pot-bellied. Every household had only five or six vessels and two sets of clothes – if they were lucky. They had bears, owls and monkeys, who were in such bad shape. I was taken aback that so close to Delhi, where we are steeped in privilege, lies this village in abject poverty,” she says.

Geeta and Kartick eventually investigated the illegal practice of dancing sloth bears from 1995 to 1997. They stayed in over 60 villages across five states — Bihar, Odisha, Karnataka, Haryana and Rajasthan.

“We realised right at the very beginning that if we wanted to help implement India’s wildlife laws to eradicate the illegal and brutal practice of dancing bears, we had to work with the nomadic community that depended on the bears for a livelihood,” says Delhi-based Geeta.

Geeta adds, “Kartick and I travelled for months to remote parts of India, stayed in tents and on railway platforms to gather intelligence. The dancing bear practice was being handed down from generation to generation, thereby preventing youngsters from accessing education. We wanted to ensure a bright future for younger generations while ensuring sustainable protection of the bears.”

The duo’s report was published in 1997 and submitted to the government of India, which got them their support and cooperation. It also helped them establish the world’s largest rehabilitation centre for sloth bears in Agra in 2002.

“The first of the bears started coming in on Christmas Eve in 2002. That was a beautiful blessing. Interestingly enough, our last bear also came in on Christmas Eve in 2009,” Geeta says.

In 2009, the final curtain was drawn on the centuries-old practice in the country, and Wildlife SOS successfully rescued and rehabilitated 628 sloth bears from this cruel industry.

However, a lot of the bears were already infected with tuberculosis. “The Kalandars had tuberculosis, and hepatitis was endemic in the community, and the bears would live with them in their huts. About 50% of the bears were lost due to these diseases. But today, all of the bears in our enclosures are almost 20 years old, with a few turning 30 and 32,” says Geeta, who continues her work to resolve man-animal conflicts.

Helping The Kalandars

To protect the indigenous sloth bear population, efforts had to be made at different tiers. An alternate means of livelihood confirmed uprooting the practice effectively.

At first, the Kalandar community felt threatened by the Wildlife SOS team, who they thought were attempting to take away their only means of survival.

“In the beginning, they couldn’t understand why we wanted to help them, and it took us many years to earn their trust. Whatever little Kartick and my salaries permitted, we used to take small things like helping them with rice or atta. If a village needed water or a tubewell, we’d help them with that. We even helped them make ad hoc temporary toilets, which were essential for the women. Over time they realised that we wanted to help provide a more sustainable solution for their families,” she says, adding that funding from donors and international organisations came only after 2002.

Slowly, the community began to adopt alternate methods of livelihood.

“There was a very old man who took the funds to buy himself a Genset which he would lease out at weddings or events. Highway stalls of boiled eggs and omelette stations and other food items, juice stalls, fruit and vegetable carts were set up. The women were empowered with many skills, seed funds for their small businesses like sewing, block printing. They always did better than the men in accepting this change and turning their investments into profits,” says Geeta, who also helped set up a driving school for the youngsters who learnt how to drive auto-rickshaws.

Along with providing alternative livelihoods for the community, Wildlife SOS has designed and carried out several initiatives to empower the women of the community in Rajasthan, Madhya Pradesh, Haryana and Uttar Pradesh.

Geeta adds, “We wanted to wean them off child marriage practices. We asked them how much they spent on marriages, and it was maybe Rs 6,000 to 8,000 at the time. We then assured them that we would pay for the girl’s lehenga and kitchen vessels only if they waited till their daughters were 18 before marrying them off. They agreed.”

Even today, the organisation has to approve 100-200 seed funds and marriage funds every year.

Banks were another foreign concept for the community, which had a low ratio of students completing their education. “In many villages, if the child has cleared his class 8, they can avail of loans from the block officer. So we put them in touch with the authorities, which made them more willing to study. We even pay for everything from the satchel to the sweater to their pens, books and fees on the condition that they educate the girl child too,” says Geeta.

Over 3,000 families have benefited from the initiatives by Wildlife SOS, and over 7,600 children access education which helped change the future for the community.

The Return of Elvis

Wildlife SOS rehabilitated all 628 sloth bears in four large natural sanctuaries across India. Wildlife SOS operates these centres in collaboration with the State Forest Department. They were also able to stop the poaching of the bear cubs from the forests successfully.

But even today, there is a community across the border in Nepal that still indulges in the dancing bear practice. During some festivals, they cross the border and come into some states.

In 2015, the Wildlife SOS anti-poaching unit, ‘Forest Watch’, gathered intelligence about a gang of poachers who had a bear cub in a remote village on the Indo-Nepal border area.

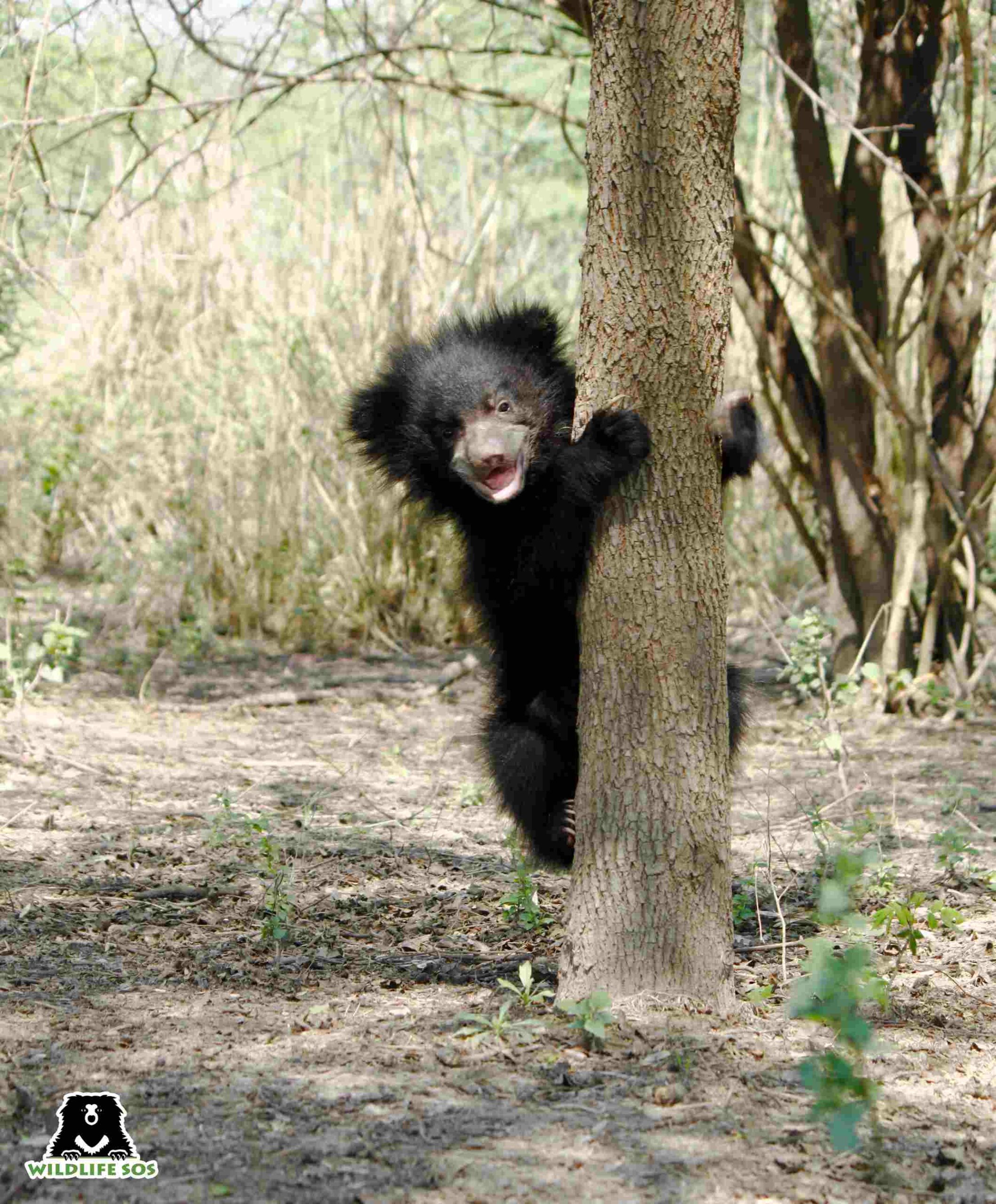

“We liaised with the Forest Department and local police to launch a joint operation to rescue the cub, who was later named Elvis,” says Geeta, who adds that the King of Rock and Roll was her ‘heartthrob’ growing up.

Elvis was poached from the wild as a cub of barely 6-8 weeks old and was in the process of being smuggled across the international border. His delicate muzzle was already pierced with a red hot iron poker.

“Unfortunately, the poachers had already received word of the raid and had fled the scene before the Forest Department and our team could intercept them. We found Elvis chained to a tree, whimpering softly and scared of being left alone in a half-starved condition,” she says, adding, “Elvis has been hand-reared by our staff and caregivers since then. We can’t release him back into the wild. As he was snatched away from his mother at such a young age, he never had the chance to learn the basic skills of surviving in the wild.”

“Today, it fills my heart with joy to see Elvis, who is almost five years old, living a healthy and safe life in the company of other bears at the Agra Bear Rescue Facility,” says Geeta.

The septuagenarian describes her journey as a ‘roller coaster ride’ and is still not ready to throw in the towel when it comes to conservation. “I am aware that there is still plenty more to come, and I feel incredibly fortunate to have experienced so much, connected with so many lives and been able to make a difference, no matter how small it may seem,” she signs off.

(Edited by Vinayak Hegde)

If you found our stories insightful, informative, or even just enjoyable, we invite you to consider making a voluntary payment to support the work we do at The Better India. Your contribution helps us continue producing quality content that educates, inspires, and drives positive change.

Choose one of the payment options below for your contribution-

By paying for the stories you value, you directly contribute to sustaining our efforts focused on making a difference in the world. Together, let's ensure that impactful stories continue to be told and shared, enriching lives and communities alike.

Thank you for your support. Here are some frequently asked questions you might find helpful to know why you are contributing?