Breaking The ‘Colour Bar’: When Malcolm X Joined An Indian’s Fight Against Racism in UK

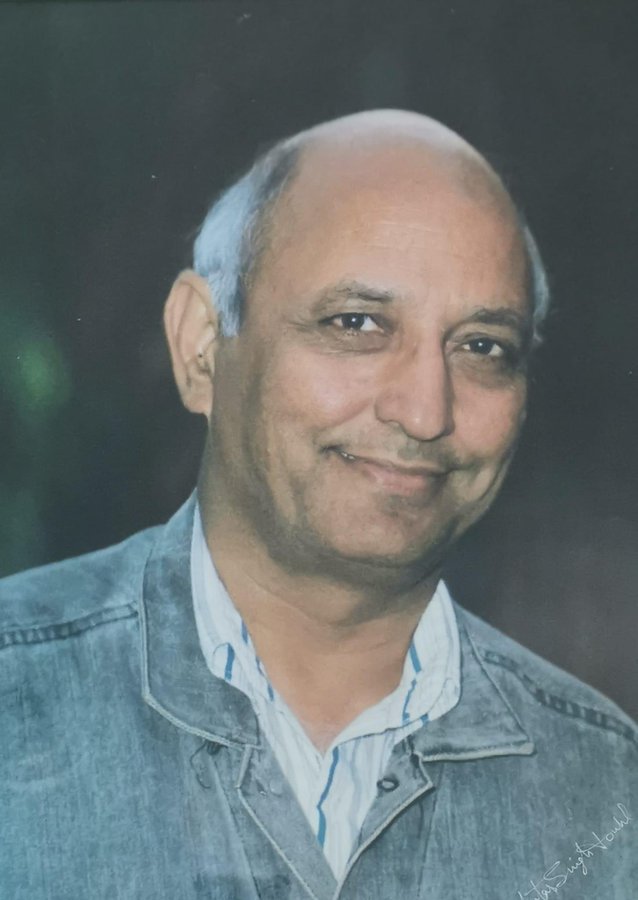

On 8 October, Indian-born activist Avtar Singh Jouhl OBE passed away. Singh was a trade unionist who valiantly advocated for workers’ rights and spent his life battling racial discrimination in the UK.

Barely nine days before he was shot in New York, on 12 February 1965, American civil rights activist Malcolm X arrived in Smethwick, an industrial town near Birmingham, England, on the invitation of an Indian-born trade unionist.

The civil rights icon showed interest in visiting this town after reading disturbing news reports about “coloured people” being “treated badly”.

Malcolm X wanted to witness with his own eyes the racism endured by immigrant foundry workers from South Asia, who were unable to access decent housing and endured rampant racial discrimination in public spaces as well as the “colour bar” in pubs and factories — the practice of forcing non-white persons into segregated spaces.

In Smethwick, the activist visited Marshall Street, where there were posters put up by local estate agents stating “Whites Only” or “No Coloureds”. Upon seeing them, Malcolm said, “This is worse than in America. This is worse than Harlem. In New York I haven’t seen such things, but there we have other attacks and discrimination against Black people.”

Fearing for Malcolm’s safety in a town that didn’t take too kindly to his presence, the Indian trade unionist expressed fear that local white residents may want to physically harm him. To prevent such a thing from happening, he offered Malcolm the protection of his organisation — the Indian Workers’ Association (IWA).

Being the fearless leader he was, Malcolm refused his offer.

Later, the activist and the trade unionist visited a pub named The Blue Gate, and the former would later recall:

I ordered a drink and the barmaid already knew me and she said that, ‘My [landlord] doesn’t allow Black people to drink here. You can have a drink in the bar’ … Malcolm X said there was no point, and we walked into the bar where several IWA members were. He had a soft drink and chatted with different people about the colour bar. He was there for 15 minutes, and he said, ‘Keep up the fight. The only way to defeat the colour bar and racism is to fight it back.’

It is said that Malcom X’s visit to Smethwick highlighted the racism deeply embedded in white British society, particularly the “colour bar”.

In the words of this Indian trade unionist, Malcolm’s visit was “the shot in the arm for the anti-racism struggle in Britain” and “put racism in Britain on the international map”.

The trade unionist who made this happen was Avtar Singh Jouhl, whose activism and role in the IWA brought racism to the forefront of the British national discourse during the 1964 general elections.

His activism played an important role in helping fast-track laws against racial discrimination like the Race Relations Act, 1965, which outlawed discrimination due to colour, race, ethnic or national origin in public places, as well as Race Relations Act, 1968, which focused on eradicating discrimination in housing, employment and advertising.

Namastey Smethwick

A native of Jandiala village in present-day Jalandhar district of Punjab, Jouhl grew up with three brothers and sister in an agricultural household with little to no formal education. While his siblings worked on the farm, Jouhl was sent to study in school and earn a formal education.

In an interview with International Socialism in 2019, he recalled, “My family was actively involved in the Indian pre-independence movement. My cousin was imprisoned in 1941 for five years by British authorities. While he was on the run before 1941, the police kept raiding my family house and taking my parents and other relatives to the police station, questioning them and beating them. That was my early childhood as I remember it.”

Enrolling at Lyallpur Khalsa College in Jalandhar in 1953, he became a member of the Student Federation of India (SFI), taking on a variety of issues including rising fees and poor facilities for students, while also organising with local peasants and industrial workers.

Similar Story

India’s First General Election & More: 8 Iconic Pictures Capturing Indian History

NA

Read more >“In 1956, my uncle returned from Britain and his idea was that I go for higher study, so he sent me to England. My brother was already living in Smethwick and that’s how I came to the West Midlands. I came in early 1958 and although I was married, my wife didn’t join me until 1960. She didn’t want me to come to England. My brother and my father-in-law were already here and they said, ‘You are starting your classes in October, in the meantime you can work,’” recalled Jouhl. He was only 16 when he wedded his wife Manjeet in an arranged marriage.

Arriving in England, the objective was to enrol at the London School of Economics.

“My situation was unique — most of my contemporaries didn’t come for education, they almost all came to work. Back home, the Partition of India caused pressure on land and there was a lack of jobs. People from the Commonwealth had no restrictions on their entry into this country until July 1962. As long as they had an Indian passport, they could come and settle here,” he said.

Encountering racism

Jouhl’s first major encounter with racism came during his first visit to a pub in Smethwick called the Wagon and Horses. This experience would inform much of the activism that would follow.

I went to the toilet while they went into a room and I didn’t know which room they went into. I came out of the toilet and went into the assembly room. As soon as I opened the door, there was a whole crowd of white men staring at me and the landlord came and shouted at me, saying: “Your people are in the other room.” I went into the other room rather than arguing with them and asked my brother and others: “What is this, why can’t we go in that room?”

They said: “We aren’t allowed in that room.” I asked them why and they said, “White people don’t like us sitting in the same place.” My next experience was when I went for a haircut in Brasshouse Lane in Smethwick. As soon as I opened the shop door, the barber came to the door and said: “No. We don’t cut your people’s hair, only white people.” So I was really disgusted. Back in India I had never experienced this sort of abuse. I was really angry and sad.

But that racism wasn’t just exhibited in pubs, but also in the way “coloured people” were unable to access subsidised public housing. Even in the foundry where Jouhl worked, there were separate toilets for non-white workers.

At his workplace, South Asian immigrant workers were compelled to undertake dangerous work, but for much less pay and position than white workers.

Challenging racism

Jouhl’s “life-changing” moment would come in the form of an advertisement for the IWA, a workers collective not affiliated with any major trade union or government agency, which campaigned against racism. He found this advertisement in a food package delivered to him and housemates.

He joined straight away without any hesitation and rose through the ranks quickly. Given his formal education and fiery spirit of activism, he rose to the position of general secretary of the IWA’s UK branch in 1961 — a couple of months after his wife Manjeet joined him from India.

Speaking about one of the first things he did in the IWA, he said, “To test the colour bar in the pubs, we organised pub crawls involving members of the IWA and student organisations from Birmingham and Aston universities — so a mixture of white students and Asian workers.”

“The students used to go in the pub first and get the drinks, and four or five Asians would go in later and be refused after being given some excuse like the room being reserved. The students would then come to the counter to challenge that. Using that evidence, we opposed the publican’s licence when it came up for renewal, because under the licensing law the licensee cannot refuse to serve people in such a blanket way,” he added.

Meanwhile, with regards to accessing housing, “Avtar would keep track of which landlord refused to rent out their places to them and when it was time for their permit renewals, Avtar would provide evidence to the board of their racism and they would lose their permits,” noted Brown History on Instagram.

As Jouhl explained in another interview, “A couple of landlords’ licenses were refused and that got huge publicity in 1963, because up until then, racial discrimination was not unlawful so everyone and anyone was free to discriminate.”

On the political side of things, the IWA campaigned for the Labour Party to support a law against racial discrimination, for which they even faced resistance from white union workers.

Jouhl was also involved in breaking the “colour bar” at his own workplace by employing some “big lads” to physically push aside the guy responsible for overseeing the segregated toilets. Even though he didn’t mind getting fired for his actions, his employers were “too scared” of him.

David Jesudason, a British-Asian freelance journalist who covers race issues, noted in a May 2022 article, “The colour bar may be Britain’s most shameful secret. While many people in the UK now see apartheid and segregation as part of other countries’ histories, few are aware that up until very recently, non-whites were barred from certain jobs, shops, pubs, and even toilets.”

“Buckingham Palace, it was revealed last year, banned ‘coloured immigrants or foreigners’ from serving in clerical roles in the royal household until at least the late 1960s. The Race Relations Act of 1965 sought to end public discrimination, but private clubs — such as the Smethwick Labour Club — could still legally ban non-whites,” added Jesudason.

Of course, changing the law didn’t rid Britain of racism. In response to the “colour bar”, the first Desi pubs built by Sikh landlords came into existence.

As Jouhl recalled in an interview with Jesudason, “You can play Indian songs here. It was not possible in a white pub.” These Desi pubs still exist in different parts of the country, but are multicultural spaces that accept all.

Over the following decades, Jouhl continued to battle racism in public spaces across the UK. Although he had first come to England to study at LSE, he ended up spending nearly three decades working in foundries across the Black Country (an area of West Midlands county in the UK) before becoming a senior lecturer of trade union studies.

In the midst of all this, he never stopped organising, educating and fighting for the rights of immigrants and battling racism.

“Jouhl, under the guise of the IWA, fought various immigration acts that barred entry from ‘Black’ countries and ensured the organisation he was a secretary of became a ‘darling of the Punjab’ by fighting for Indian workers to be given British passports — it’s one reason why Windrush deportations have featured fewer British-Asians. And it’s possibly the reason that a man who always agitated against the state was given an OBE [Order of the British Empire] by the Queen in 2000 for service to trade unions and community relations,” wrote Jesudason.

Last week, on 8 October 2022, Avtar Singh Jouhl, passed away at the age of 84. How can one sum up his legacy? It’s probably this quote from an interview with Jesudason.

“Any racist law has got to be opposed, violated and broken. There’s no point in a ‘democratic process’ if that process is producing these laws. But I don’t think I’m brave — I just have the instinct of the working class.”

Sources:

‘Life-long class fighter against racism’- An interview by Sheila McGregor and Esme Choonara; Published on 17 October courtesy International Socialism

‘Breaking the Color Bar — How One Man Helped Desegregate Britain’s Pubs (and Fought for an Anti-Racist Future)’ by David Jesudason; Published on 16 March 2022 courtesy Good Beer Hunting

Birmingham Black Oral History Project– An oral history interview with Avtar Singh Jouhl

Brown History/Instagram– Avtar Singh Jouhl

Images courtesy Twitter/Taj Ali/UCU

If you found our stories insightful, informative, or even just enjoyable, we invite you to consider making a voluntary payment to support the work we do at The Better India. Your contribution helps us continue producing quality content that educates, inspires, and drives positive change.

Choose one of the payment options below for your contribution-

By paying for the stories you value, you directly contribute to sustaining our efforts focused on making a difference in the world. Together, let's ensure that impactful stories continue to be told and shared, enriching lives and communities alike.

Thank you for your support. Here are some frequently asked questions you might find helpful to know why you are contributing?